The struggle for the American dream

The Museum of Culture and Environment exhibit inspired by immigration and conflict

October 13, 2016

The opening of the Museum of Culture and Environment was a showcase and celebration of one of our strongest assets as Americans: diversity. On Sept. 29, the Museum of Culture and Environment in Dean Hall opened with a celebration full of food, art and fun from different parts of the world; in particular, South American countries from Mexico to Chile.

The opening of the Museum of Culture and Environment was a showcase and celebration of one of our strongest assets as Americans: diversity. On Sept. 29, the Museum of Culture and Environment in Dean Hall opened with a celebration full of food, art and fun from different parts of the world; in particular, South American countries from Mexico to Chile.

Museum Director Dr. Mark Auslander emphasized the focus of diversity on the displays, “We’re really trying to celebrate the fact that we are a diverse campus, so we’re bilingual and lots of things are in English and Spanish here, and these are just beautiful.”

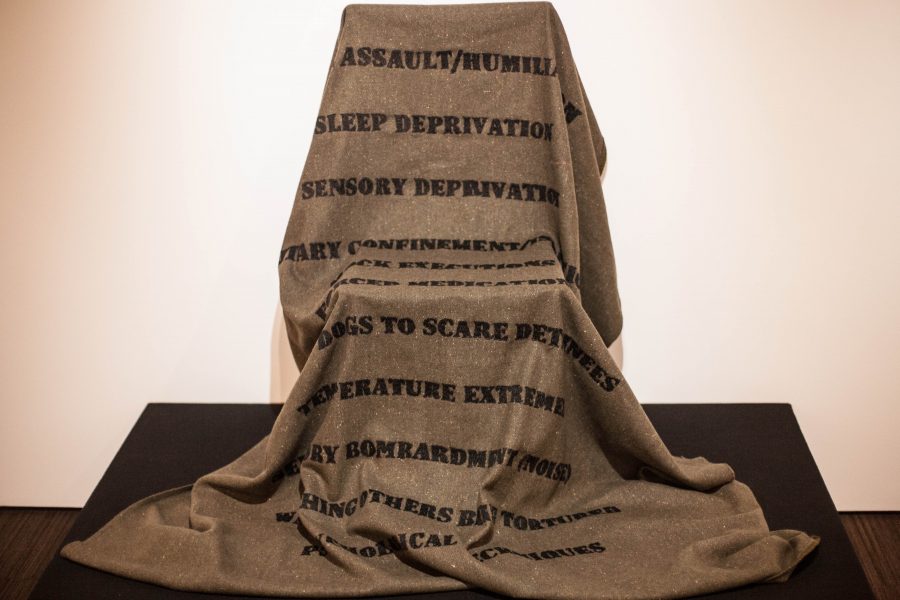

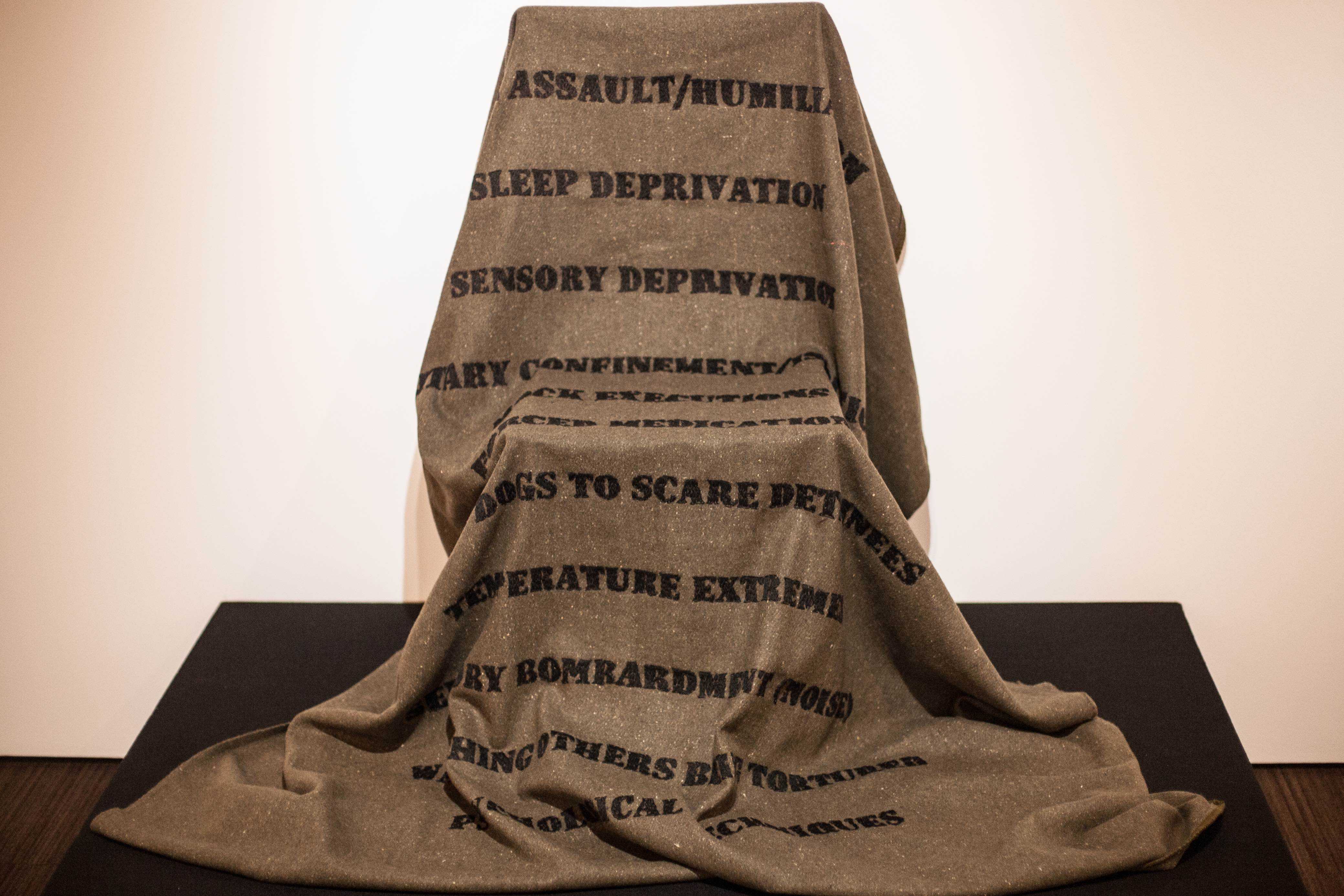

After visitors ate their fill of culturally diverse entrees, they took a few steps and entered the museum to experience all the diverse displays it has to offer. The museum’s first exhibition of the year is titled “Tapestries of Hope.”

Visitors observed many different sewn tapestries that referenced a violent military coup that took place in Chile in the 1970s, which we know now was backed by the CIA. During this coup, hundreds of young men and women—targeted for their political activity—were abducted and tortured by their captors and their bodies were never found. The victims were rightfully named “The Disappearers.”

The mothers of the missing, who did not have a way to protest without the fear of death, made burlap stitchings dedicated to the crisis they faced. These burlap sewings told the stories of “The Disappearers” and often depicted children’s clothes but no children were present in the artworks. The stitchings read with the hard-hitting words, “Where are they?” However, these artful protests weren’t sewn in vain.

“They started to smuggle [the burlap stitchings] abroad, and that’s really what started to change global opinion about the dictatorship in Chile,” Auslander said.

Toward the back of the exhibit, visitors were shown the pain and strife of the human rights struggle of immigration into America. On one of the display tables was an immigration game, similar to Monopoly, only there’s no winning; every roll is essentially a Go-To-Jail card.

Another, more humorous piece is a look at immigration through the eyes of a Native American, which reads, “In December 2014 members of the Native American National Counsel offered amnesty to 240,000,000 illegal white immigrants living in the USA. A road to citizenship was extended by the native counsel to the European population, in this land, those without criminal records of contagious diseases.”

Other pieces are heavier, such as a poster of a Mexican border wall with Uncle Sam looking over it, expressionless, watching some Mexican citizens harvest their crops. After visitors finished checking out the exhibits, several speakers took the stage and gave their take on immigration and culture from a first-person perspective. One of those speakers was Toño, who decided to keep his last name censored from the public for safety reasons.

Toño said, “I want you to know that I came to this country when I was 14 years old. I did not want to come to the U.S. I never wanted to come; I hated English. I never had any interest in coming to the United States, maybe to come to visit — I felt fine over there. My mother came to work as a maid and my father was working in a factory. I lived with my grandfather. Then they sent for me. I came to the U.S. alone.

I was excited and it felt like an adventure to travel alone, but then, when I got off the bus in Tijuana, on the Mexican border, was the first time I felt alone. There was nobody there to receive me. All I had was a memorized phone number of the coyote [or one who secures passage across the Mexico/U.S. border] who was going to get me across. I don’t know how much my parents paid him. At first he didn’t answer and I had to sleep on the streets. I felt alone and, I am not going to lie, I was afraid. Here I am, this kinda big guy, and I was afraid. I cried myself to sleep as I was thinking that ‘los hombres no lloran [men don’t cry].’

The next day I called again and the guy met me. There were seven other people crossing that night; it was a nightmare. We tried three times to cross before we were successful. It was January and it was really cold at night. I was hungry, and dirty, and afraid. When I finally hugged my mother, I felt like a little kid. I was so happy and I thought the worst was over, but let me tell you that the worse is not over. I am afraid for my parents. I do not want them to get deported. They worry everyday about themselves and about me. My sister was born here in Washington and is a citizen, but I am not. I am a DACA student, but I know my status can change. And a lot of people are talking about building a wall and I have to stay quiet because now I don’t know whom to trust. In my classes, I am more careful now. I know they can hear my accent and I don’t want to open that door of having to answer questions.

What I want you to know is that I work, I go to school, I pay taxes [and] I follow all the laws. I feel like I am contributing to this country and want a real opportunity to struggle towards the American Dream. I want you to know that breaking up families is never a good thing for anybody. I know so many hard working people who fear deportation. My parents are older now, and what are they going to do if they are sent back? I want you to know that I am American like you.”