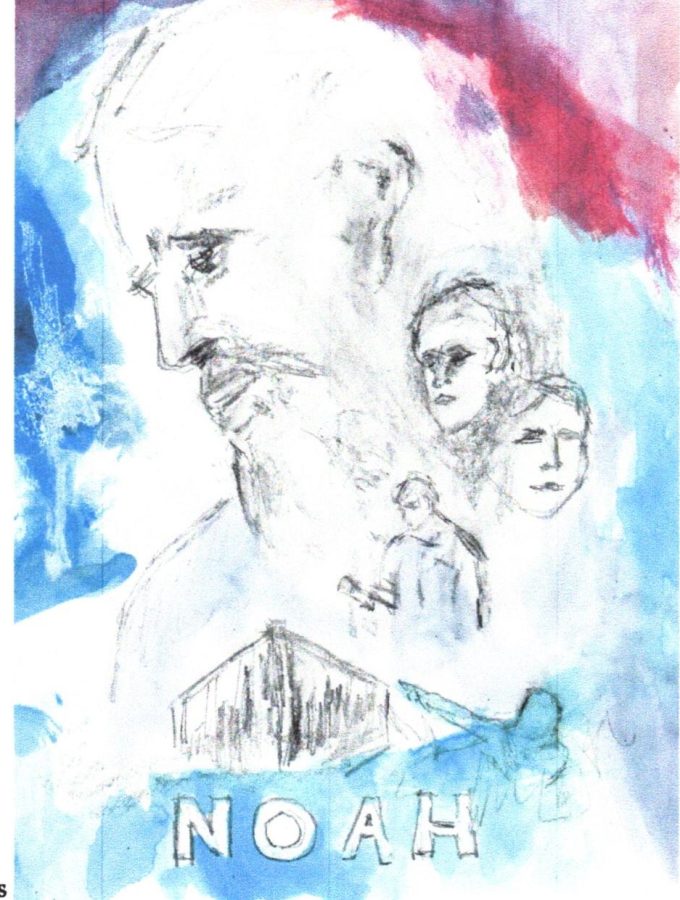

Make it new: A response to Aronofsky’s “Noah”

February 27, 2023

Darren Aronofsky’s 2014 film, Noah, has generated considerable controversy for deviating from the original depiction of events in the flood story, as related in the Tanakh (or Old Testament). How much of the film is an accurate portrayal of the episodes detailed in Genesis 6 through 9 and how much of it is the creation of the director and his co-writer, Ari Handel? The four chapters in Genesis that concern Noah take about ten minutes to read, while the run time for the film is 138 minutes. After analysis, much of the physical activity and character development in the film is the product of Aronofsky and Handel’s imaginative story telling.

Why would they make changes to the original story? In an interview in The Atlantic, “The ‘Terror’ of Noah: How Darren Aronofsky Interprets the Bible,” Cathleen Falsani claims that it is the messages, not the history, that matters.

She quotes Aronofsky: “I think it’s more interesting when you look at not just the biblical but the mythical that you get away from the arguments about history and accuracy and literalism. That’s a much weaker argument, and it’s a mistake. But when you’re talking about a pre-diluvian world—a pre-flood world—where people are living for millennia and centuries, where there were no rainbows, where giants and angels walked on the planet, where the world was created in seven days, where people were naked and had no shame, you’re talking about a universe that is very, very different from what we understand. And to portray that as realistic is impossible. You have to enter the fantastical.”

I am going to focus on Aronofsky’s development of characters not present in the original story, and how these changes allow him to develop both an exciting visual narrative and a convincing solution to some of the enigmatic elements in the events as they unfold.

First, the involvement of the giants (Nephilim), called “The Watchers” in the film, in the building and defense of the ark, allows Aronofsky to introduce one of the first fantastic highlights in the story. Next, the initial infertility of Shem’s wife, Illa, and Noah’s later attempt to sacrifice her twin daughters, allows Aronofsky to develop a coherent psychological and consistent temporal narrative. And, lastly, the role of Tubal-cain as Noah’s nemesis allows Aronofsky to pit father against son, as Tubal-cain encourages Ham to murder Noah, which creates a backstory to help explicate and resolve the ambiguity in Ham’s response to his father’s nakedness in the post-flood events.

In Genesis 6:2, “divine beings saw how beautiful the daughters of men were and took wives from among those that pleased them.” In verse 4, “It was then, and later too, that the Nephilim appeared on earth.”

Scholars debate whether the Nephilim were the offspring of fallen angels and human women, or whether they were a separate race of giants, or whether they were the lineage of Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve, or whether they were aliens from another planet.

Aronofsky portrays these large “transformer-type” creatures as being made of huge chunks of rock that have a core of light, portraying these creatures as made of light that has become deeply materialized. There are also tell-tale signs of their having once had wings.

Regardless of their genealogy, they serve Aronofsky well as characters in a modern action film. There are no battle scenes in the biblical version of the Noah story, but the epic battle in the film foreshadows the upcoming stories in Judges and Kings.

Aronofsky conflates the different interpretations of the Nephilim. During the battle to protect the ark from the wicked men who God regrets having created (Gen. 5-8), the Nephilim, upon being defeated, are suddenly “beamed” into the heavens. Their fallen, embodied nature appears to be redeemed by having helped Noah and his family.

In both versions of the Noah story (Gen. 6 and Gen. 7), Noah’s sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth, have wives to take onto the ark. Aronofsky departs from this traditional depiction. Much of the dramatic development of the film revolves around finding wives for the young men.

Early in the film, Noah and his wife rescue a young girl, named Illa (portrayed by Emma Watson), who is still alive after a brutal rampage of her village by the warriors of Tubal-cain. Illa has an abdominal wound; later, she finds herself to be barren. A romantic interest develops between Illa and Shem. Noah goes to a village to find wives for his other sons, but he is repulsed after seeing young women sold for food, and he returns empty handed to tell his family that they will be the last humans.

My favorite new character is the one-eyed crone, played by Aronofsky’s seventh grade teacher, Vera Fried, who confronts Noah in the village and gives him her fierce English teacher look, shouting, “You! You!”

Noah is in the firm belief that God wants all humanity dead, but Ham rebelliously runs away to find a wife. Meanwhile, Noah’s wife, Naameh (Jennifer Connelly) connects with Grandfather Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins) and explains the dilemma; later, searching for berries in the forest, Methuselah bestows his blessing on Illa, and she becomes fertile. Ham (played by Logan Lerman) befriends a young woman, but in the commotion before the flood, she is abandoned. Disheartened by his loss, Ham blames his father, and a rift develops between father and son.

Beyond extending the theme of romantic love (a modern and not a biblical notion), the conflict between Ham and Noah extends the theme of the transfer of the father’s lineage to his sons, a theme that was posited at the beginning of the film.

During an interrupted ceremony, where Noah’s father, Lamech, is passing his lineage to his son, a sacred snakeskin talisman is lost. In Aronofsky’s rendering, this heirloom is stolen by Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone) and is later given to Ham, who, at the end of the film, gives it back to Noah. Rightfully, it belongs to Shem, since he is the firstborn. Ham relinquishes his place in the family structure and, like Cain, becomes a wanderer. Aronofsky works in another touch of Cain and Abel allegory, when Shem (Douglas Booth) is sent by Noah to find his brother and returns without him.

Tubal-cain is mentioned in Gen. 4:22, as the one who “forged all implements of copper and iron.” Not all Tanakh lists agree, but in Gen. 4:22, Tubal-cain is listed as a son of Lamech; in Gen. 5:25, Methuselah is said to have begot Lamech; in Gen. 5:29, Lamech begot Noah;—so, Tubal-cain would be Noah’s older brother (or older half-brother, since the name of Noah’s mother is not mentioned). Aronofsky’s understanding of Tubal-cain being a worker in metals connects to the iridescent material that is being mined in the film. There seems to be shifting technology in play.

One of the most tenebrous parts of the Noah story is in the post-flood stage, after Noah has become a drunkard (Gen. 9:21). It is here where Ham views his father’s nakedness. These events have spawned an ongoing debate around whether there was a rape of Noah by Ham, a castration of Noah by Ham, or that Ham “seeing his father’s nakedness” (Gen. 9:22) is to be interpreted only as sign of disrespect in seeing Noah in an immodest pose.

Aronofsky has set the stage for the latter, more literal interpretation. Noah feels he has failed God by not keeping his promise to end humanity because he failed to sacrifice Illa’s twin daughters. Aronofsky does not emphasize God’s command, “Be fertile and increase, and fill the earth” (Gen 9:1). Noah’s failure to understand God’s plan, combined with a full dose of post-traumatic stress, has led him into drunkenness.

In the Falsani interview, Aronofsky said: “Noah just follows whatever God tells him to do. So that led us to believe that maybe they were aligned, emotionally, you know? And that paid off for us when you get to the end of the story and [Noah] gets drunk. What do we do with this? How do we connect this with this understanding? For me, it was obvious that it was connected to survivor’s guilt or some kind of guilt about doing something wrong.”

This is plausible enough, although the film raises as many questions as it solves. Whose brilliant idea was it to get the animals to lie down? Is the curse of Canaan (Gen. 9:23) now extirpated? How does Methuselah, a mortal, become the healer of infertility and not an Angel of the Lord? What might happen with this altered gene pool? With the seas rising due to global warming, is God rescinding his covenant?

But, as they say, “It’s only a movie.” Regarding the last question, only time will tell.