Students ask for more active shooter training, the university responds

Spencer Brown, Vice President of the Cybersecurity and Ethical Hacking Club, asks a question to the university officials during the open student form on Feb. 14.

February 20, 2019

CWU is working on creating an emergency situation training video in response to the Feb. 6 active shooter false alarm. Answering students’ questions during an open forum on Feb. 14, CWU Police Chief Jason Berthon-Koch said the video will include information about what to do in the event of an emergency, how to communicate with others and where to get reliable information.

“Part of my goal with the video education is to instill and show students and faculty and staff where official information is going to come from,” Berthon-Koch said.

Berthon-Koch fielded questions together with President James L. Gaudino, Provost Katherine Frank and Chief Information Officer Andreas Bohman during the forum organized by the Associated Students of Central Washington University (ASCWU) to talk about the series of events that shut down the Ellensburg campus between 5:35 p.m. and 7:27 p.m. on Feb. 6. For two hours, gathered in the SURC Pit, students were able to voice their concerns about what happened that evening and discuss how the university will handle future emergency situations.

Many students who attended the discussion said that the university currently lacks in educational preparation for emergency situations. They also critiqued how CWU handled communication with the public both during and following the false shooter threat.

CWU Police Chief Jason Berthon-Koch answers a student’s question during the Feb. 14 ASCWU forum regarding the Feb. 6 active shooter false-alarm. During the discussion, Berthon-Koch addressed many common concerns students had regarding the police response and timeline of events that night.

LACK OF TRAINING

One of the most prominent questions asked was about the lack of training for students.

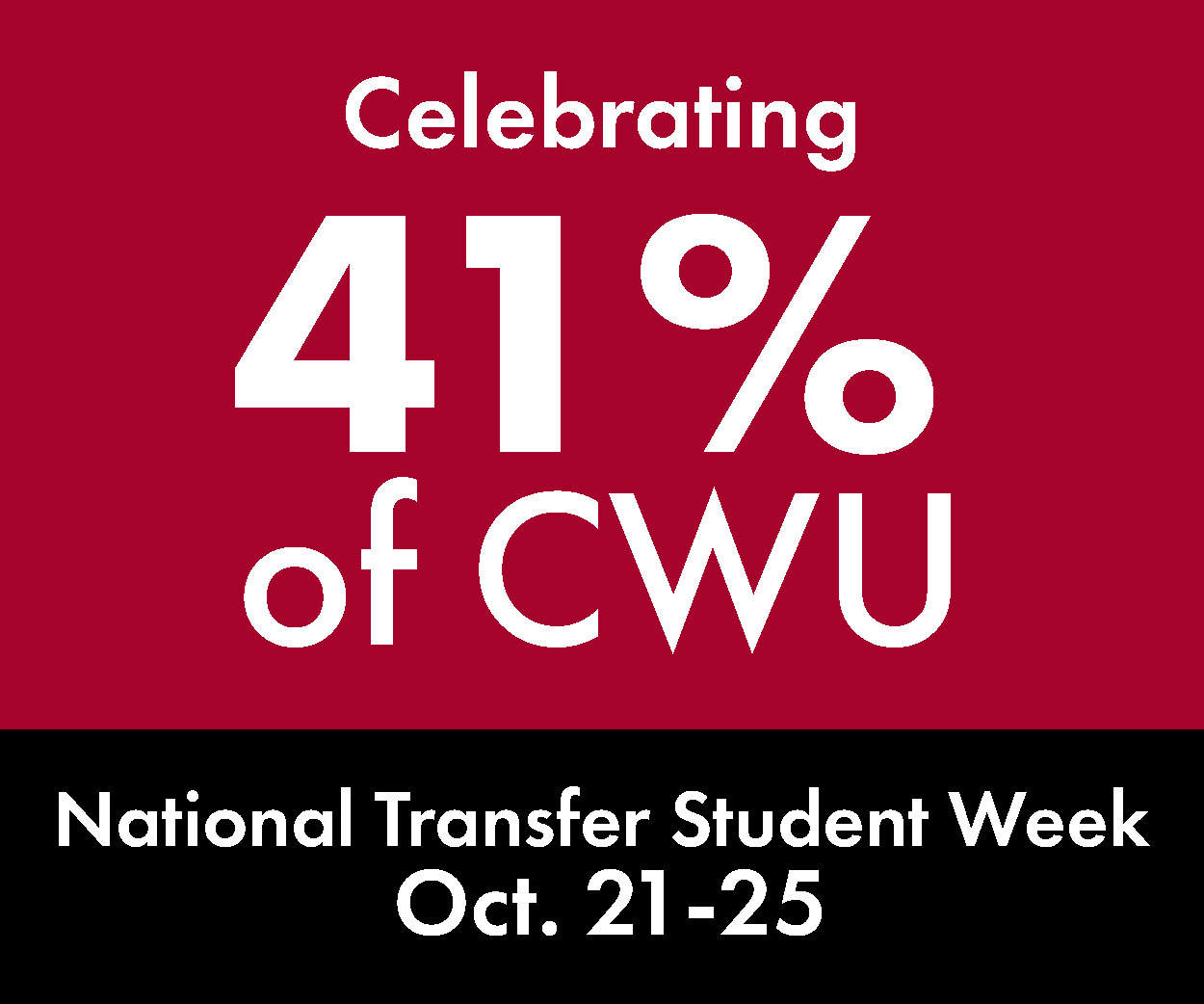

Traditional freshman students are required to attend a session during Wildcat Welcome Weekend that explains what to do in the event of an active shooter situation. CWU senior Samantha Berheit noted that transfer students do not receive this training. She suggested offering this training once a year for the duration of a student’s time at CWU might be beneficial in educating more students.

CWU student and Vice President of the Cybersecurity and Ethical Hacking Club Spencer Brown also called for more student training.

“If students don’t know what to do, they panic,” Brown said. “In an emergency, you revert to your lowest level of training.”

Brown suggested that an emergency training video be shown to students on a quarterly basis. Although this might seem repetitive, it’s better for students to immediately know what to do in an emergency than to hesitate or put themselves in danger.

LACK OF OFFICIAL COMMUNICATION

Other students expressed concerns regarding how the university handled official communication with the public during the two hours the school was on lockdown.

Twitter was the go-to form of communication the university used between the original and final RAVE Alert! messages. Bohman understood the concerns students had with Twitter as a legitimate news source during emergencies.

“We thought that communicating with Twitter was a viable alternative,” Bohman said.

Bohman also noted that the CWU Police and Parking Twitter account was spoofed during the active shooter threat. These accounts were pretending to be “actual, authoritative sources” when in reality they were not verified or run by CWU and were posting unconfirmed information.

“We can’t turn off Twitter, but we can certainly make sure that we communicate more effectively,” Bohman said.

In an effort to organize information on Twitter, Public Affairs Coordinator Dawn Alford posted a tweet on the official CWU Twitter account with the hashtag “#CWUActiveShooter.” A student raised a question about the effectiveness of a hashtag during a legitimate emergency situation. The CWU official Twitter only used the hashtag twice. Hashtags can be used by any account on Twitter.

ASCWU President Edith Rojas listens to senior elementary education major Bailey Malizia ask a question about the public getting information from police scanners. Rojas spearheaded the organization of the event along with the President’s Office.

MISINFORMATION ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Another issue brought up at the forum was the way social media played a part in escalating both the situation and the fear of some students.

“Twitter created emergency,” Gaudino said regarding the two-hour lockdown on Feb. 6.

Gaudino said that during the event, he simultaneously had Twitter, police scanners and the CWU police radio open. Rumors spread of the situation on Twitter faster than Gaudino or the CWU police could verify.

“We were overwhelmed [by social media],” Gaudino said. “We knew within a minute that we had lost control of that environment.”

Gaudino and Bethon-Koch both addressed the issue that police scanners are not always valid forms of information in an emergency. According to Gaudino, scanners that were giving information about local hospitals deploying their active shooter protocols were misinterpreted on social media. For example, Twitter users reported that students were being airlifted when in reality hospitals were only preparing helicopters in case they needed to airlift shooting victims.

Berthon-Koch explained that police scanners are often operating on split frequencies, which means that a person listening to a single police scanner stream is only receiving a portion of the information. Berthon-Koch also said that police jargon varies from district to district and can be easily misinterpreted. When CWU police were reporting the “all-clear” on scanners, they were only clearing specific buildings which had reported threats.

Misinformation on social media makes it difficult for emergency responders to respond to events because there is no clear channel of information.

“If you don’t see it firsthand, please don’t tweet it,” Berthon-Koch said. “You can put people’s lives in danger.”