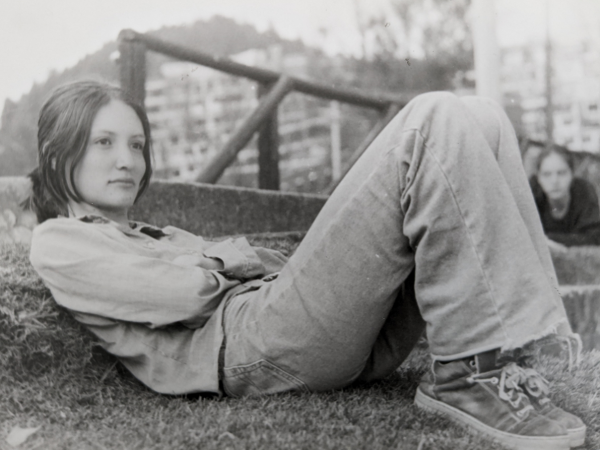

In the fourth volume of a running series, Dr. Claudia Mendez Wright discusses her experience growing up in Colombia, her journey in coming to live in the US and her connection with her home country.

Claudia Mendez Wright

Dr. Claudia Mendez Wright is a professor of sociology who’s been working at CWU for about a year and a half. Wright attended Universidad de los Andes (University of the Andes), the University of Louisiana and Utah State. Wright grew up in Bogotá, the capital and largest city of Colombia.

“I grew up in the 80s, and Colombia in the 80s was really dangerous,” Wright said, “[There were] two big drug cartels and armed militias that targeted the civilian population. Ultimately the ones who pay are the most marginalized populations in our country. That was the environment I grew up in.”

Despite the privilege that Wright feels she grew up with, her family was still affected by the state of the country. “I was able to go to school, I was able to get an education and my parents had decent jobs. However, the economy still wasn’t great, so my parents struggled. When they got divorced my dad decided he couldn’t afford the education he wanted to give us, so he migrated to the US,” Wright said. “At that time, the immigration laws weren’t as they are today, so he was able to work with a permit.”

One thing that is very important for Wright is the way her background shaped her to view the world around her. “I thank my country for giving me vision. I think that is something that is being lost. Maybe it’s the Culture Industry that Theodore Adorno talks about—it keeps us so entertained that we’re not able to have a vision for what’s happening,” Wright said. “I think growing up in Colombia makes you really aware of the importance of education and how to use privilege to improve yourself obviously, but also to improve your family and to give back. ”

While attending Universidad de los Andes (University of the Andes) in Colombia, Wright went on to work in marketing, “I loved it, but there was always something missing. I wanted to own the research I was doing. In the private industry, it’s not really yours, ” Wright said. “So I decided to migrate to the States and get a PhD to become a university professor.”

“I applied to some Master’s programs in the States … I did get in, but they wouldn’t give me funding. As a Colombian paying for education here is impossible,” Wright said. Despite the previous disappointment, Wright reached out to the Director of Graduate Studies at the University of Louisiana. Within the day, he got back to her saying that while the deadline to apply had already passed, he would look into finding funding for her. “In like two days he calls me to tell me he has funding for me.”

He said that he wanted Wright to be there and helped her find a job doing marketing at the Art Museum. Two months later after all of her paperwork had been processed, Wright was on her way to Louisiana. “I showed up with two bags in the airport. The Director of Graduate Studies picked me up and put me in a dorm. I slept that night without covers or anything because I didn’t own anything, and that’s how my life started here.”

The years Wright spent at the University of Louisiana were amazing. “I had a blast. It was, I think, two of the happiest years of my life,” Wright said. At the university, she met a community of people, mostly international students from all over the world who became her friends, “We partied a lot!”

After her master’s, she moved to another state to pursue a PhD program but describes her experience at the university, which she has chosen not to identify, as extremely toxic. “I stayed there for a year and it was a disaster,” Wright said. “I was the only international student. It was an extremely toxic program where some professors and students would roll their eyes whenever I would bring up my experiences from Colombia. It was just a toxic, horrible, disgusting environment. You just don’t learn in an environment where you feel othered and racialized. And they made it really evident. ”

Wright felt miserable there, but in the middle of all these challenges, she met the man who is now her husband of 15 years. She got married and decided to leave the program. “I had it really hard for a while, as I felt that I had lost my North,” Wright said.

Wright continued working in the marketing field in Colombia while still living in the US for a while. She said that as an immigrant, even being privileged in having an education, finding work in the US was difficult without the connections that come from “living in the country that you are born in I was sometimes reduced to the fact that I spoke Spanish instead of my skills as a professional

Eventually, Wright got connected with a group of people doing marketing and started teaching at Utah State in the business school. “It was a reminder of how much I like research and I like teaching,” Wright said. While she loved marketing, Wright decided that she would enjoy it more if she could do her own research. “Inspired by this and my experience with motherhood, I decided to go back to start PhD program again, but this time in sociology, because I am a social scientist.”

Wright began her PhD at Utah State and thrived. “I think when someone believes in you and doesn’t look down on you because of your identity, it makes a big difference,” Wright said.

After completing her PhD, Wright came to work at CWU. She liked that it was so close to Seattle and Vancouver, as well as the diverse student base and her colleagues. Since working at CWU, Wright has enjoyed the job and being able to make connections with the diverse community.

Wright goes back to Colombia once or twice a year and stays for a good chunk of time. “I want my daughter to learn about my culture,” Wright said. “I want her to learn more Spanish and I want her to learn what Colombia taught me, which is the drive and positive ambition, not just to get money or to succeed, but that the world can actually be a better place. I think Colombia gave me a lot of that. Colombia gave me the vision, but the US opened a different path for me. I think a combination of that is important.”

“Normally when you think about immigrants, you think of people that just leave and don’t ever go back. But for many immigrants migration makes us live two simultaneous lives. Women in my research describe how being a migrant is like being split in half, especially when you have those deep connections to your country and to your new country. It’s like your mind and your heart and everything else is divided. It makes a cool mix out of you. You belong yet stop belonging to both places. You’re not here, you’re not there, you’re just everywhere.”

Rodrigo • Feb 20, 2025 at 5:48 am

Great