The department of art and design is holding a faculty exhibition, being showcased from Nov. 14 to Dec. 14 in the Sarah Spurgeon Gallery in Randall Hall. Before the opening of the exhibition, three professors whose art is being displayed, Marcus DeSieno, Gregg Schlanger and Jaqueline Trujillo, gave small lectures on what their art represents to them and to the community they’re reaching.

The first speaker was DeSieno, who displayed his photography skills through hacking into satellite cameras and other expressions of photography. DeSieno started his talk by telling a story on how he stayed with a stranger, a migrant that he saw struggling on the side of the road. While waiting for an ambulance for the stranger that man had passed away. When the ambulance came 90 minutes later, the paramedics said, “Illegals die out here all the time.”

DeSieno went searching for reasons why these things are taking place. “This callous indifference to life shocked me to my core and started me on this path of discovering the horrors of taking place south [of the] border,” DeSieno said. He found much of it came from harmful policing tactics.

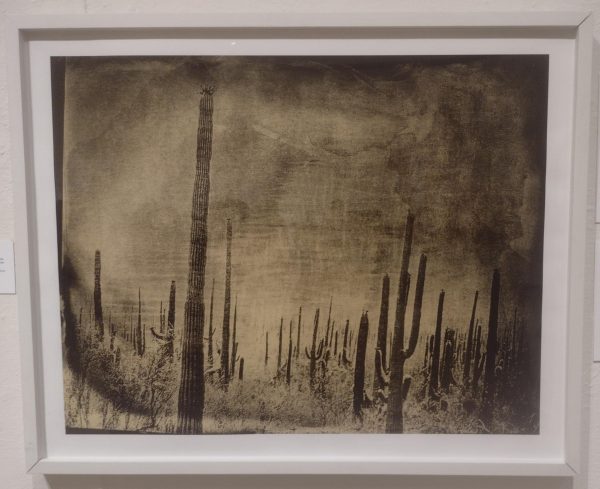

“Prevention through deterrence… This is a draconian approach to hyper policing the border in select areas,” DeSieno said. “To purposefully redirect migrants into the most dangerous and hostile sections of the border … the open deserts of the southwest and the unpopulated wilderness of southern Texas.” While asking questions, DeSieno found this policy to be one of the reasons why border crossing is so deadly for migrants.

“This policy has not prevented migrants from crossing into the United States but has instead led to a humanitarian crisis,” DeSieno said. “Where the United Nations has now declared the US-Mexico border to be the deadliest land crossing in the world.”

DeSieno brought attention to this issue at CWU through this exhibition. “I recognize and acknowledge my personal politics are probably very different than a lot of you here,” DeSieno said. “When making this work, I want to bring all this information to the viewer. I’m interested in finding some common ground in an increasingly polarized United States. And for me, it starts with this. Nobody should be dying out here.”

DeSieno chose to use his art to protest and raise awareness on these conditions. “I’ve been using these photographs and words from my conversations [and] interviews to raise awareness and apply pressure to government officials,” DeSieno said. DeSieno spends his summers volunteering in California, Arizona and Mexico, providing water to migrants, giving first aid and working with search and rescue. He also helped in the shelters in Mexico.

The next artist who spoke was Gregg Schlanger, who also did outreach with his different types of art in communities. He talked about making concrete molds of endangered small animals with kids up in Providence, RI. Then he made bricks and created two towers in Rugby Gates, which is a neighborhood on the north end of Memphis, TN as a tribute to the water tower that had been there.

“But what I thought I would focus on in this short time is public art, which is the other side of my practice,” Schlanger said. Schlanger has created many public art pieces for communities to come together and enjoy.

“[I] worked with a number of kids,” Schlanger said. “So part of what I enjoy doing is working with the community as much as I can and letting them get part of the creation of the work.” Schlanger seemed adamant to explain that the art he would plan wasn’t only for the community, but also to include the community in creating it.

Schlanger not only did outreach in communities but in schools as well, and brought kids from inner cities to learn how to create art. “There was a selected neighborhood, Smith Hill,” Schlanger said. “Which was selected [because it] was a really rough area in… Providence, and through a grant in the city… a number of kids were hired to work with me.”

The last speaker was Jacqueline Trujillo, who worked in mixed media art. She’s also a resident artist at Gallery One. “My work is a personal narrative that attempts to expose the fallacy of memory,” Trujillo said. “Reveal the value of familiarity, confront uncanny recollection and embrace nostalgia.”

Trujillo’s work was strongly influenced by her childhood home. “I use the juxtaposition of natural and man-made landmarks to trigger nostalgia and familiarity from these locations and to provide a contextual environment,” Trujillo said.

The challenge to keep the memory that was once so clear as a child. Trujillo shared that as she grew, her art of her childhood home morphed into different colors and aspects. “My work began to change and evolve as I re-evaluated my childhood home,” Trujillo said. “And how perspectives made all the difference in memories.”