In the Equipment Circulation Center (ECC) in Lind Hall, film students linger, talk about their upcoming projects and check out cameras, tripods and microphones from senior film major Michael Boyer. Recently 22, Boyer is the lone employee at the ECC, and more often than not has to turn away his peers from equipment that would normally be available to them, and give them subpart equipment.

“I’ve had to turn away so many prod three students for equipment because I’m just reserving boom poles for prod six people,” Boyer said. “That should not be the case. When I was in prod three, I was able to get boom poles, and other students in the past were able to get boom poles.”

For context, the film program has six core classes to take: Production classes which students will refer to as “prod one,” “prod two” where students begin to develop their skills and onward up to “prod six,” where students make their thesis film. Right now, Boyer has to make the call on his own which production teams get which equipment, and with three currently broken boom poles out of seven — which are used to record audio — there’s not much wealth to go around.

Boyer said that he has had to give lesser equipment to four prod three groups this quarter. In a class with three people per group, that’s 12 future filmmakers without the means to hone their skills.

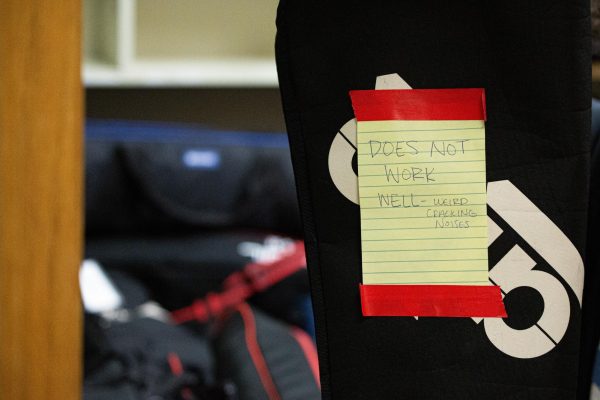

Filled to the brim with equipment stamped with sticky notes denoting their damage and unwalkable due to zero floor space, Lind Hall 118H is dedicated to storage of the film program’s equipment, both broken and usable, which Boyer says makes things more complicated than they need to be. Boyer estimates that about 90% of the equipment here is broken. The storage room was moved to 118H from 118G, which Boyer says is much bigger, and allowed for much easier access to the old equipment.

“I don’t know [why we keep it around],” Boyer said. “I feel like there was a system that we followed before this that made sense … some of these [notes] are very specific, like ‘weird crackling noise, got it,’ but then this one is like ‘out of service.’ What is that supposed to mean? Is it something that we can fix? We’re not really told to throw away anything, just label it.”

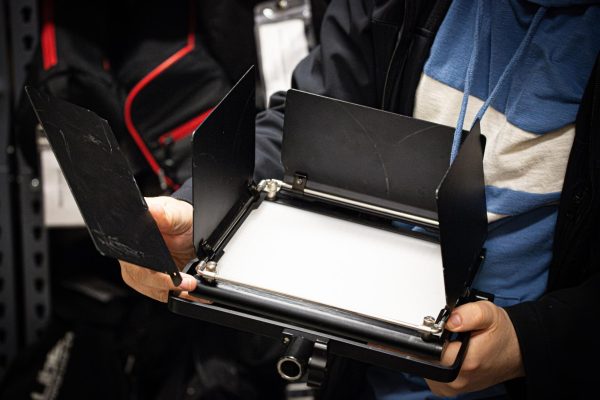

Boyer said that there was an instance where working black flags — which are used to block out the sun for the camera — were just sitting in the storage room. He put them back in the ECC after he found them.

Yohannes Goodell, a senior film major, said that when equipment does come back broken, it’s more often than not due to tenured usage rather than student error.

“A lot of the equipment we have … is under constant use and constant wear,” Goodell said. “Stuff breaks … the boom equipment, which is like our sound equipment for the sound pole, we checked that out thinking that it was okay, then during the shoot [there was] a huge rattling noise and the top of the mic kept coming on and off, so we had to jerry-rig it to make it work.”

When equipment does come back broken, there is nobody on campus trained to fix it. And despite protocol, there is nowhere to bring it to get repaired.

“I’m technically supposed to take [equipment] away and repair it, but I have not been trained on how to repair equipment,” Boyer said. “We don’t have anybody to repair equipment … If it’s broken, I can’t do anything about it. Or if it’s something that’s slightly broken but could still work … for budget sake, I have to keep it in.”

Another issue that film students at CWU face is the lack of cameras designated specifically for filmmaking. When the CWU film club hosts their quarterly 72-hour film bash, where club members have exactly three days to put together a short film, the ECC is barren, with quality cameras being the most sought-after and least available asset.

“There was nothing,” Boyer said. “No cameras, no lights, all the batteries were gone, all the C-stands were gone … Everything was gone. I had to say ‘Oh, you can use the Nikons.’ … That’s the thing, we have mostly Nikon cameras and Nikon cameras are photography cameras … A lot of times students don’t want them and I understand because a lot of them are older Nikons too. This equipment is pretty old, maybe like six years old, maybe older than that.”

Many students felt like they had been manipulated in their choice to attend CWU for the film program. Boyer said that the photos on the department’s website page are a decade old. Some photos include RED cameras, which are the industry standard and not available at the ECC.

“They lied to us,” Yami Rodriguez, a junior film major, said. “They promised us RED cameras and when I got here they had none.”

Boyer also believed that the website is misleading to prospective students. The department website touts CWU’s film program as one that will “prioritize providing you with a hands-on approach to film education, where you will have access to modern equipment and experienced mentors who are passionate about the art of filmmaking.” This is a far cry from the reality many film students are facing.

“I don’t want to sound like we’re whining and want money,” Boyer said. “But when you market yourself as a film school, and that you’re providing that opportunity for people, you’re basically scamming people.”

Despite a lack of proper equipment and false advertising for the department, film students have high praise for their professors, including Professors Phan Tran and Michael Caldwell, who have done well in preparing them to enter the film industry.

“Caldwell right now in prod one has been teaching them how to use a camera, how to use all the equipment itself,” Sophomore film major Javier Angulo said. “Which is really good because it shows that there are professors here who really do care and want you to get the experience … I was thinking of leaving in the winter quarter, but thanks to Phan for actually teaching me something in winter quarter, I stayed for the spring. Big shout out to Phan.”

Senior film major Lindsie Avalos echoed Angulo’s praise of Caldwell and Tran as well as shouting out Professor Jason Tucholke. She also alluded to the importance of the professors in their choice to attend CWU.

“I’d say our professors really try,” Avalos said. “That’s the one good thing about our program is our professors. Jason [Tucholke]’s awesome, Caldwell’s awesome, Phan’s awesome. We have really strong professors that actually care about us and that really keeps us going. If it weren’t for them, I think most people would have dropped. I really do think so.”

Many of the film students thanked Tran for his generosity in buying equipment for them out of his own pocket, and in some cases even lending out his own personal equipment.

“He’s helped out a lot to allow us to make something that we are actually proud of,” Boyer said. “We can make good art. There are really talented people here, and if they just get equipment like [Tran’s], or even more advanced equipment, we could make some really cool stuff here. It just sucks that a lot of this shit is either broken, old or outdated.”

Boyer expressed love for a professor who has since departed from the program named Justin Daering, who he said made himself available to every student in the department. Even those whom he didn’t have classes with.

“He fought for us, and for the students,” Cirillo said. “He made an effort to learn everyone’s names. I never had a class with him and was in the ECC one time and he comes up to me and introduces himself. He’s like ‘I’m Justin, what’s your name? Nice to meet you, welcome to the film program.’ He was such a caring teacher, and again it was just this one interaction that I had with him this one time I met him, and I could tell immediately he cared about every one of his students.”

Daering stopped teaching at CWU in the spring of 2022. Amongst the film program runs a widely subscribed to theory that he was let go due to his pressure on administration to support the film program.

“In spring 2022 it was announced that he was going to be not returning anymore,” Boyer said. “It’s basically theorized that he was let go because of how much he was actually fighting for the film program. And the school didn’t like him speaking his mouth, and they let him go. They didn’t fire him, they just didn’t renew his contract because he was very outspoken on the treatment of the film program.”

Avalos toured the film department in the spring of 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic. According to her, the program seemed to be alive and thriving at the time, not like it is now.

“This place was really packed with film students,” Avalos said. “It was alive, and I think COVID definitely was a big part of ruining the film program. It really struck it down. I’ve heard [Professor Michael] Caldwell say the same thing. There was a film club and then it just died, and then the film club was reborn in my junior year.”

Boyer recapitulated her sentiment, describing Lind Hall as “feel[ing] like the skeleton of something that used to be really great.”

Beyond the damaged and old equipment, other issues remain. Namely, a lack of in-person professors and the content of these remote classes. Angulo said that during his first year, his prod one class was only available online.

One recent assignment posted on Canvas by a remote professor for an editing class was titled “Crisis on Campus Editing Documentary assignment.” This assignment required students to edit together footage from a 17-minute video of a faux school shooting. The video opens up with young adults running away from their campus and being shot by a man on the roof, without a content warning.

“I literally said ‘Oh my god’ audibly,” Boyer said. “I thought I was watching people actually get shot … I’m personally okay with watching that content, but there was no content warning. It didn’t say what it was. It was just called ‘Crisis on Campus,’ and that could mean anything.”

“We had to do research on it to make sure it was fake,” Rodriguez said. “[They] gave us not even a week, like a few days.”

Despite concerns, the love among the film program for each other as students, peers and friends is vast. But, if they had not known that they would meet the friends they have along the way, Cirillo, Angulo, Avalos and Boyer all said that they would choose another school if they could do it over again.

“I didn’t have the money to go somewhere else,” Rodriguez said. “So I would have been stuck here anyways … And if it wasn’t as okay as it is now, then I probably would have not been in this major, I probably would have done something else.”

“I was like, ‘Why am I here? Maybe I should go somewhere else. Even Eastern [Washington University]’ and I’m not even a big Eastern fan,” Avalos said. “But there was a time where I did think about it because it doesn’t feel like the school actually cares about us … We see that a lot in the favoritism towards the theater department.”

Avalos said that she was skeptical about last year’s merger with the theater department, but held out hope that it could possibly lead to better funding. Avalos, among other students, took issue with the school’s handling of the film department during the recent GiveCentral donation campaign, in which the theater department got $8,000 and the film department got $600.

“I didn’t really think much was going to change, and I was right.” Avalos said. “It definitely pisses me off. I’m not going to benefit from it [because I’m graduating], but it pisses me off for the program and for my friends that are here and that are going to continue … They’re only fundraising for one camera? That’s very pathetic. We need more than one camera.”