HUNTING FOR MY INNER ELK

February 6, 2023

In the process of examining a particular artwork in a gallery, the mind wanders and then comes back into attentiveness; and when this attentiveness is extended over a period, a sense of losing oneself becomes a state of absorption.

In a mindfulness meditation, one tries to observe whatever comes into awareness, one’s feelings and thoughts, without holding onto or pursuing them. Mindfulness meditation is usually approached as an attempt to tame the mind, but if the mind is relaxed, there is also an aesthetic experience in play.

Howard Barlow, who teaches 3-D Design at CWU, frequently collaborates with his wife, Lorraine Barlow. As a thought experiment, I posit my extended viewing of “Lorraine and Howard Barlow’s “Lock, Stock and Barrel” (2022), recently on display at the Sarah Spurgeon Gallery in Randall Hall, as a mindfulness meditation.

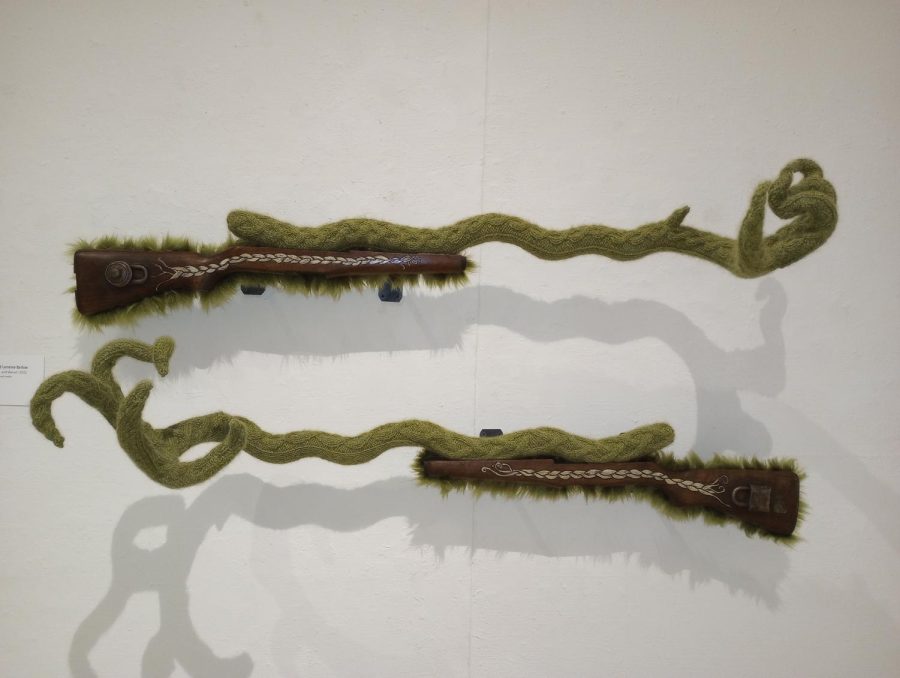

This composite sculpture “Lock, Stock and Barrel” is a visual pun. The title itself is a merism (a figure of speech) that combines three contrasting parts to represent a whole. In this case, it means everything. “Lock, Stock and Barrel” consists of a pair of imaginative hunting rifles (his and hers, I suppose) consisting of different materials. Each “stock” is a bolt-action rifle stock minus the hardware, painted with a delicate, woven design and trimmed in fake fur. In the butt of each rifle is an embedded “lock” (a combination lock), and the barrel of each rifle is a four-point elk antler with an olive-green wool covering knitted in a cable stitch.

As a whimsical foray into a surrealistic world of consciousness, “Lock, Stock and Barrel” reminds me of one of Gary Larson’s “The Far Side” cartoons, where the usual suspects are in reversed relationship to one another.

There is a tactile language at work here, and I want to touch this sculpture because there is a quality to this artwork that moves beyond the visual information projected, but as with most artwork in a gallery, I must stand at a reasonable distance and take it in with my eyes.

The pair of sculptures, each about four feet wide mounted on the wall, have a strong design element, revealing fine craftsmanship, and the sensuous curves of the rifle are sure to have a certain heft familiar to anyone who shoots.

However, the conventionally blued barrel one would expect as the horizontal extension to a rifle is contorted by the angular nature of an elk’s antler that form different patterns and are enigmatically covered in wool, rather than the expected tissue of bone and cartilage.

As my eyes move around the sculpture, these different aspects of color, line and form suggest a satirical commentary on our American gun culture while, at the same time, I am emotionally in a suspended state of active involvement, experiencing the sculpture’s dimensionality and the perceptual awareness that is accompanied by intuitions of passing time unfolding in space which I perceive in the immediate present being a retention of perceptions just past, and this retention in the present overlapping with the perception coming to be, not isolated from others or fixed alone in time but flowing into each other, continually becoming different, go nowhere, as I return to where I began, standing in front of the sculpture, now with a smile on my face.

George Santayana in “The Sense of Beauty” developed the idea that an aesthetic experience is one that does not involve pleasure for a specific part of the body, but is rather “a lifting out of ourselves” and an appreciation that involves no wish to possess what is being appreciated. He says, “A first approach to a definition of beauty has therefore been made by the exclusion of all intellectual judgments, all judgments of matter of fact or of relation.”

Aesthetic and moral judgments are classed together in contrast to intellectual judgments; they are both judgments of value, whereas intellectual judgments are judgments of fact. Santayana makes a distinction between aesthetic and moral values, between work and play—work will be action that is necessary and useful, while it will seem that the play is frivolous.

To the contrary, he argues, “For it is in the spontaneous play of his faculties that man finds himself and his happiness.” It is in the contemplation and appreciation of beauty

that I find my true self.

The interplay between mind openness and mind focus is echoed in the concept of play by

Friedrich Schiller. In “On the Aesthetic Education of Man,” Schiller tries to show the development of mankind through a series of stations, from the physical to the rational, and he believes that the aesthetic experience will develop a human being’s moral behavior.

In the fifteenth letter, Schiller claims that “play” is the principal expression of the human spirit and that it reconciles the divisions which civilization has produced in the human condition. Schiller divides the creative impulse into the desire for sense (the body), the desire for

form (the mind) and the desire for play.

He believes that the development of the play impulse reconciles the dichotomy: “Reason demands, on transcendental grounds, that there shall be a partnership between the formal and the material impulse, that is to say a play impulse, because it is only the union of reality with form, of contingency with necessity, of passivity with freedom that fulfils the conception of humanity.”

How to raise human consciousness to this level is the challenge, but a sustained aesthetic

appreciation of reality and the nature of mind through meditational stability would be a start. Meditation and art allow one to freely relate to both the inner and outer worlds.