“Halloween Ends”… Thankfully

October 26, 2022

After much anticipation, Oct. 14 saw the release of “Halloween Ends” in theaters and on Peacock. Directed by David Gordon Green, the film marked the conclusion of the recent “Halloween” trilogy, which was a continuation of the original film directed by legendary director John Carpenter. I have liked the two previous films in the trilogy, “Halloween” (2018) and “Halloween Kills” but sadly I did not like this film at all.

Picking up three years after the end of “Halloween Kills,” the film picks up with iconic final girl Laurie Strode played by Jamie Lee Curtis trying to move on from Michael Myers and go back to the life she had before in Haddonfield.

No spoilers will be discussed here for the sake of myself.

In concept, it could work. But in execution it falls flat on its face.

Jamie Lee Curtis delivers another great performance, she oozes charisma as she has for the last 40 years. Andi Matichak, who plays Laurie’s granddaughter Allyson, delivers her best performance of the trilogy. She finds herself essentially the main character of this movie and rises to the challenge.

The plot is extremely messy, inconsistent and at points inconceivable. Characters make decisions that just don’t make sense. Not in just the horror-movie-decisions way, but in the this-character-would-not-do-this way.

For a brief non-spoiler example, Laurie tries to set up her daughter with someone who has been shown to be a dangerous person to be around. The same Laurie that isolated herself for decades because of her fear of Michael.

The filmmaking is hit-or-miss. At points it is maybe the most well-made “Halloween” movie since the original and at others it’s one of the sloppiest movies I’ve ever seen. Some editing decisions just don’t make sense. Despite this being the longest movie in the series, the script feels like it was chopped in half.

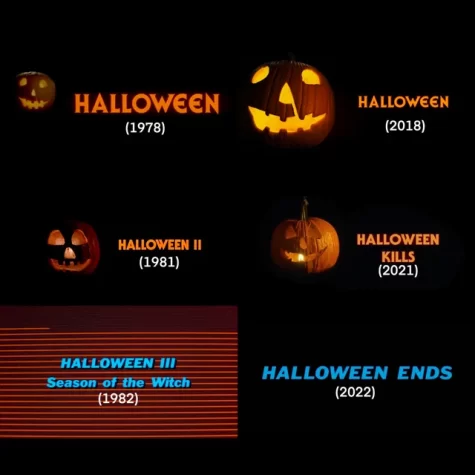

There is a very clear parallel that Gordon Green has tried to achieve between this trilogy and the original three “Halloween” movies.

The first of each trilogy follows nearly the same story beat for beat: Michael commits a crime, goes to prison, breaks out years later on Halloween night and is on a collision course with Laurie. The second film in each trilogy features a far higher kill count than its predecessor and has Laurie in the hospital for the majority of the movie.

With “Halloween Ends,” Gordon Green essentially confirms that this parallel was his goal. The third film in the original series was “Halloween III: Season of the Witch,” which notoriously does not feature Michael Myers. The film has since been reclaimed as a cult classic, but at the time it was an incredibly divisive decision that left many audience members confused and angry.

This film does feature Michael Myers, but the choices that Gordon Green makes in the film very much indicate that he knew audience reaction would be stark and may even be what he wanted.

“There’s a lot of people that when they see an ending like that [“Halloween Kills”], or that kind of unresolved chaos, they get frustrated as a moviegoer,” said Gordon Green in an interview with SFX Magazine. “For me that’s just part of the fun … Any frustration that was expressed about about the last one [Halloween Kills], I just kind of smile and say ‘Hold tight, here we come.’”

The title cards for each film in Gordon Green’s trilogy also mimic the title cards for the original three films, which becomes incredibly clear with “Ends” featuring a neon-blue italicized font that is also featured in “Season of the Witch” departing from the bold orange font used in the first two films of each trilogy.

Maybe I’m just playing right into Gordon Green’s hand. Maybe this reaction is exactly what he wanted, and if that is the case, I commend him. But for all the storymaking decisions that could be considered bold or daring, the film ultimately falls flat due to its extremely poor execution. It doesn’t matter how many times you swing while you’re at-bat if you don’t actually hit the ball.